So I flicked through my UMA library and chose Children: Rights and Childhood by David Archard to work through. I noticed on Amazon that a third edition was published in 2014 with a bunch of updates, so depending on how I find the edition I have (1993) I might follow up with that.

OK, so as per usual, bold indicates direct quotes, the rest are my real time notes with first reading.

Firstly, Archard dedicated this work to his mum, which occurred to me as being significant considering the subject matter. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how work in this field, and the potential/opportunity/nature of activism related to concepts of childhood and adult/child dynamics passing down from one generation to another, and it seemed meaningful that at the start of the book he says:

“In fond memory of my own childhood this book is dedicated with much love to my mother.” (p ix)

It’s an interesting area and to consider. I’ve wondered a lot about what conditions cause tipping points for people to become ‘cycle breakers’ in regards to adult/child dynamics – how much their own relationships with their parents and childhood experiences may or may not factor in. And how a person’s experience of childhood makes a difference in terms of their awareness of the social justice issues relating to the experiences of children. How their relationship with their own parents (if they have one) can make progress in their own relationships with their children easier, or more difficult.

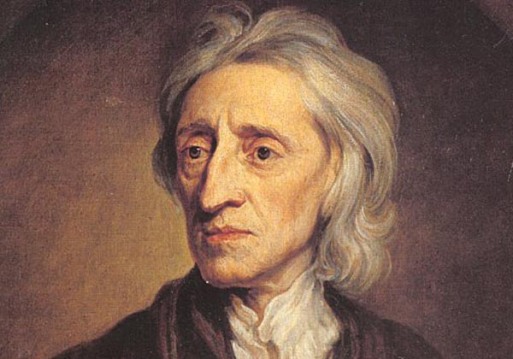

The first chapter is entitled ‘John Locke’s Children’ and I’m starting there.

“John Locke (1632-1704) is arguably the the most important and influential figure in the history of English-speaking philosophy… He did not write a philosophical treatise on childhood although he did write Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) with recommends the appropriate education for a young gentleman. These recommendations are surprisingly modern and liberal, permitting Some Thoughts to be viewed, along with Rousseau’s Emile (1762) as the earliest manifesto for a ‘child-centred’ education.” (p1)

and

“typical of most philosophers…his account of childhood has to be extracted fro scattered remarks, and is not to be found explicitly and systematically expressed in a single work. Moreover, what Locke has to say about children in one context does not always sit easily with what he has to say about them in another. These tensions are due to writing about children from different perspectives. In this respect Locke’s is fairly typical of much contemporary philosophical writing on childhood. Locke writes of children as the recipients of an ideal upbringing, citizen’s in the making, fledgling but imperfect reasoners and blank sheets filled by experiences… Similarly, model writers seem often to demand of their ‘children’ that they be different things, according to the aspect under with they are being regarded.” (p1)

So many interesting points raised so early into the chapter! I’m not going to comment here too much on the citizen’s in the making/blank slate business, because I have a feeling more of that is going to come as this chapter goes on. But this part:

“what Locke has to say about children in one context does not always sit easily with what he has to say about them in another. These tensions are due to writing about children from different perspectives. In this respect Locke’s is fairly typical of much contemporary philosophical writing on childhood.” (p1)

strikes me so much. Over the last years of reading writing about children and childhood, this is probably one of the stand out issues for me – that at different times and for different reasons, children become what the author wants or needs them to become.

To me this signals an absence of awareness from the author of the personhood of children, and persists in relegating them to the status of property, even when the author otherwise claims to be child-centred/respectful etc. It is so frustrating to read what appears to be progressive writing on childhood/parenting/children’s experience, for it just to again, seem evident that the underlying notion remains that children are still the property of the adult or institution – there to fit with the particular perspective at the time rather than to participate with their own agency, or be consistently recognised as a full person in their own right. The dynamic of the belief that on the basis of their age they are a thing to be done to, rather than a person that you might work in partnerhsip with, resurfaces time and time again.

“…let me sketch the various circumstances in which Locke wrote about children, how these different accounts roughly hang together and where difficulties begin to arise for a consistent overall theory of childhood.” (p2)

An Essay concerning Human Understanding (1689) (p2):

- all human knowledge comes from single source: experience.

- Locke denies that any knowledge is inborn.

- Young children show no awareness of things that other philosophers had claimed to be innate.

- Knowledge acquired from experience, therefore acquired gradually.

- “Human’s become knowledgeable reasoners; and childhood being a stage in the developmental process whose end is adulthood, children would seem to be imperfect, incomplete versions of their adult selves.” (p2)

The above ideas, especially that children as a group are ‘imperfect, incomplete versions of their adult selves’, are interesting to me in unpicking origins of the marginalisation and diminishing of children’s experiences in current social norms and values.

In the first of his Two Treatises of Government (1698) (p2):

- criticises Robert Felmer’s “patriarchal account of political authority as bequeathed by God to Adam, and thence to his descendants, the kings.

In the second Treatise (p2)

- defends his own view that civil government be founded upon and limited to the freely given consent of rational individuals.

“Yet, if political power should not be thought of as parental, Locke readily conceded that parents should have power over their children, who did not yet possess the rights of adult citizens.” (p2)

Archard goes on to make the point:

“If the extent of legitimate political power is limited by the rights of the governed and the power ends of government then should not parental authority be constrained by the rights of children and the due purposes of parenting?” (p3)

This is mega and is explored more in the chapter. I have so many thoughts on this but it’s past my bed time so they are going to have to wait.

Second part of my notes on

Second part of my notes on